The Rec

Quick Finder (Follow links for more information)

The 1922 Covenant

Bath Rugby seems to have an obsession with the 1922 Covenant which states that "no workshops warehouses factories or other buildings for the purpose of any trade or business which may be or grow to be a nuisance annoyance or disturbance or otherwise prejudicially affect adjoining premises or the neighbourhood shall at ay time hereinafter be erected on the said hereditaments". Their hearing to challenge the validity of the Covenant originally scheduled for February 2020 was postponed as part of the Coronavirus restrictions, but when it was finally held in October the case issued by Bath Rugby was under a 1925 Act, and the Judge ruled that the Act was not retrospective, so the position of the 1922 Covenant had to be evaluated according to the legislation at the time it was made. The court ruled that even with the strictest possible interpretation of how the restriction was echoed in the 1956 conveyance (rather than just being referenced verbatim) there were at least 150 addresses that were beneficiaries of the Covenant and therefore the application to rule the 1922 Covenant invalid was refused. Bath Rugby's CEO suggested that they are considering an appeal, but the Judge established that there are legal precedents that confirm that a pre-1925 Covenant is not nullified by a later Act.

Before the court case was raised there have been Tribunal hearings to clarify for the Charity Commission how the charitable land should be handled. This has resulted in a definition of the exact land area that Bath Rugby is allowed to use until the expiry or surrender of the 1995 lease, plus the definition of the size and position of the temporary extension of that area to accommodate the East Stand for nine months of each year with the requirement that for the remaining three consecutive summer months the grass surfaces must be restored in a condition suitable for playing sports or leisure uses. Furthermore the Trustees are required to limit their use of the land swap ability to land defined in the 1995 lease, and lasting for no longer than that lease has left to run. The Trustees must also not show any undue preference for any sport or organisation and not use the Recreation Ground otherwise than as an open space; and they are required to accompany any variation of the 1995 lease (which cannot have its expiry date extended) with a Condition that Bath Rugby Club must "minimise disruption to local residents and to users of the charity's land". The legal proceedings have also required the Trustees to not allow any structure on the open space of the Rec outside of the 1995 leased area plus the nine-monthly use of a defined additional area for the temporary East Stand.. This takes the 1922 Covenant a bit further, because "disruption" has a wider scope than just building on the Rec and also covers parking problems, litter and anti-social behaviour. Effectively, the subsequent legal clarifications have rendered irrelevant whether the High Court decides the 1922 Covenant should be nullified or retained.

Despite this, the 1922 Covenant was challenged again by Bath Rugby, and this time they won their case. We haven't bothered to find the case papers for that because we believe the outcome is irrelevant. It is also worth pointing out that despite the apparently successful legal efforts of Bath Rugby to get the 1922 covenant declared unenforceable, it still remains so because the conditions of the 1922 covenant are included in the 1995 lease, and the lease can be terminated (and thus Bath Rugby lose the use of the land) if they fail to observe the lease restriction "anything that may be or become a nuisance annoyance or injury to any adjoining property or its occupiers or to the neighbourhood" which is listed as an event that would nullify the lease. If the club act as though the 1922 covenant is unenforceable then the Public Trustee Act allows anybody thus disturbed to take the Custodian Trustee to court if the lease is not then terminated for breach of conditions.

Go back to top index

The East Stand Permissions

In January 2020 there was an application to renew the temporary permission for the East Stand to be installed, and this was agreed in May. The renewal asked for was for 2 years.

In March 2021 there was yet another renewal request for the East Stand and the additional temporary spectator stands. From the Trustees perspective The Trustees have to ensure delivery of Clause 4(5)(b) of the Charity Scheme: "The lease must not permit the tenant use otherwise than as a site for a temporary stand (usually referred to as Ďthe east standí) or playing pitch or access areas and must require the site to be available as open space for use for the purposes of the charity for at least three months in each year. The three months shall be consecutive summer months. The site, including all grass surfaces, shall be made available at the start of the three month period in a condition that is immediately suitable for the playing of sports and the use of the land for leisure purposes." Planning permission is required by the Town and Country Planning legislation, but it does not override other constraints.

The planning applications went before the Planning Committee on 9 March 2022. The Case Officer wrongly stated in the Committee Brief that "these legal issues are not planning matters in and of themselves". They are, because in law a Local Planning Authority is indivisible and every planning decision is legally the responsibility of the whole council. This is important because the Rec is Charitable Land, and in defining exactly how the Charitable Land shall be administered the First-Tier Tribunal (Charity) of the General Regulatory Chamber on 27 March 2014 ruled that Bath And North East Somerset Council (and any subsequent LPA that may replace it) is the Custodian Trustee of the Recreation Ground as defined in the Public Trustee Act. The Act insulates the council from responsibility for the actions taken by the Managing Trustees of the Charity. The Managing Trustees are similarly legally obliged to deliver the object of the charity which includes retaining the Rec as open ground, though with a temporary exception that the land covered by the 1995 lease (until it expires in October 2069 or is surrendered or revoked at an earlier date) can continue to be used by Bath Rugby. However it places a legal obligation on the Custodian Trustee (Section 4(2)(d) of the Act) to "concur in and perform all acts necessary to enable the Managing Trustees to exercise their powers of management or any other power or discretion vested in them (including the power to pay money or securities into court), unless the matter in which he is requested to concur is a breach of trust". It also places an obligation on the Managing Trustees "to perform any trust or duty belonging to a class which he is authorised by the rules" which in this case is the object of the Charity reproduced in full below. The Act also allows (Section 10) "A person aggrieved by any act or omission or decision of the public trustee [in most cases the Custodian Trustee] in relation to any trust may apply to ... the Chancery Division of the High Court in Chambers". Note that this is an automatic right to take legal action, unlike a Judicial Review where permission to pursue one must be applied for. As such, the Public Trustee Act needs to be included in the Legislation section of any planning application for the Rec.

The planning applications asked for a four-year extension, and the permission granted was for three years, this being considered by the Planning Committee to be adequate time for the stadium for Bath proposal to be worked up into a planning application. It is acceptable for that to be offered as an aspiration, but when the 2002 Court Order defined the Rec as Charitable Land and various Schemes modified by two Tribunal hearings by which the Trustees are required to maintain the area not covered by the 1995 lease as open space, and the Public Trustee Act of 1906 required the "Custodian Trustee" (ie the council) to take no action to prevent the Trustees from carrying out their duties, they are effectively forbidden by legislation from granting permission for building a stadium.

The minutes when published revealed that the Case Officer did insist that the covenants and legal matters were not material considerations for planning. Unfortunately, they are, because the Public Trustee Act affects all planning decisions concerning the charitable land known as the Rec, and planning decisions need to reflect the constraints on the entire council, or else the council could be paying out large sums of money on court costs for overturning planning decisions contrary to the Act. That includes permissions for any developments on the Rec outside the Bath Rugby footprint. Head of Planning needs to verify this with legal advice and then educate staff and Members of the Planning Committee.

Go back to top index

The Next Planning Application

29 September 2019: A decision on the planning application 19/03133/SCOPE has been made, and the decision is that an Environmental Impact Assessment is required as part of any future planning application for a stadium on the Rec. For those interested, the Decision Notice explains not only that an EIA is required, but also what it must cover, and provides in an Appendix the consultation responses that led to this level of detailing. We have no reservations about the decision; it was obvious that anything built on the Rec would have a significant Environmental Impact that would need to be properly assessed.

However, when we read the report in the Appendices from the Environment Agency (who own the Radial Gate; the council only manages it) we were horrified by the statement "This could for example result in the radial gate being removed". Whether this is the personal view of Mark Willitts who commented on this planning application, or the formal position of the Environment Agency, is not clear. What is relevant is that exactly how the Radial Gate contributes to the effectiveness of the Bath Flood Defence Scheme as designed by Frank Greenhalgh, is explained clearly in his document "Bath Flood Prevention Scheme" which was lodged in the Bath Reference Library. The sluice gate is a balanced mechanism actuated by floats which are controlled by the upstream water level, and provided the flotation chambers are kept clear of silt there is little to go wrong; no electrical or hydraulic mechanisms are necessary, leaving so little to go wrong that the suggestion that it is coming to the end of its life looks difficult to justify.

Nevertheless, this ignorance of what the Radial Gate is for has a long history, because in 2000 there was a suggestion that it should be replaced by a weir and the Bristol Avon Local Flood Defence Committee commissioned a hydraulic study from Bristol University and this resulted in consultants Lewin Fryer in conjunction with the Environment Agency issuing "The Hydrolab Report (Project 2281)" in March 2003. That report concluded that if the current Sluice Gate were ever removed an alternative sluicing mechanism would have to be installed otherwise the flood protection provided upstream of the Radial Gate would be lost. When the Environment Agency was part of the study that reached the conclusion that a sluice was essential, it is disappointing that they now appear to be taking the opposite point of view, without any proper research. We can only suggest that either of the documents in italics in this section are made essential reading, both for the Environment Agency staff, and for Turley who wrote the EIA assessment in the planning application and falsely described the Radial Gate as "installed in the 1970s to assist with flood management but no longer fulfils that role", when it is an essential part of that role as the Hydrolab Report proves.

13 October 2019: We were curious about how the planning application 19/03133/SCOPE, for Bath Rugby's request for a decision on whether an Environmental Impact Statement was necessary for a development on the Rec, fitted in with the reported feedback on their exhibition which made it clear that there would be an impact, thus leaving open the question about why bother to ask when the answer was already known?

Then we wondered what the Scheme for the charity Bath Recreation Ground said the objectives of the charity were, so we obtained a copy of the Scheme. We summarised that research the 2014 Hearing below. In a nutshell the Trustees are obliged to keep every part of the Rec as open land apart from the areas occupied by the Bath Sports and Leisure Centre and the area leased to Bath Rugby in 1995 plus the 1042 square metres used for the East Stand for 9 months of each year, and they can be sued if they commit a breach of that trust. Then we looked at the obligations of the council as "Custodian Trustee" and discovered that they were immune from being sued unless they condoned the breach of Trust, which would be obvious if they give planning permission for anything built on what should be open land. The planning legislation treats Local Authorities as a single unit, so the Custodian Trustee is guilty of condoning a breach of trust if the Planning Committee or any staff using delegated authority grant planning permission for a development on land required to be kept as open land.

One thing is abundantly clear: the Trustees are barred by the Charity Commission supported by both the 2014 and 2015 Court Orders, from agreeing to any building or construction on the land outside of the 3.7 acres allowed in the lease to Bath Rugby because the objects of the charity forbid it. Likewise, planning permission for any such building or construction cannot be granted by the council without the council being in breach of Trust and therefore in breach of two separate Court Orders. Legally, the idea of a stadium on the Rec is a dead duck because the series of legal rulings ensure that a Judicial Review will quash any planning permission, yet it continues to be promoted.

Thus Bath Rugby is entitled to ask for planning permission, but the council will be in breach of trust if the response is yes.

Go back to top index

The Recreation Ground 2015 Hearing

This was an appeal hearing on 18 May 2015 by the Upper Tribunal of the Tax and Chancery Chamber, as a result of the Trustees asking on a point of law for the previous judgment to be set aside and a group of local residents asking for some modifications to it because the wording was ambiguous.

The hearing recognised that there was a legal issue to be clarified, and proceeded to do so. Some of it was niceties, like whether the requirement to retain the Rec as an open space was a condition of the transfer of the land with charitable intent, or an administrative objective once the transfer was completed.

In practical terms it makes very little difference that the Tribunal opted for the latter interpretation, when the same Tribunal restricted the exception to this to the land leased to Bath Rugby and the charitable land occupied by the Sports Centre. The key difference was that as an administrative objective it was possible to allow the Sports Centre, built partly on charitable land and partly on other land owned by the council, to remain while it was a functional building and the land to be returned to open space once it had life expired, whereas as a feature of the charity there would be a requirement to demolish that part of the Sports Centre that occupied the charitable land. As a consequence of that decision it was ruled that while the Sports Centre continued to be in use it should ba a separate charity administered by the council, leaving the rest of the Rec to be administered by a different set of trustees.

Although the Tribunal found in favour of the Trustees, the amendments to the Scheme that followed the decision provided many of the clarifications that the local residents had asked for. Thus although they lost the argument that the Trustees should not be able to agree to a land swap, the clarifications limited the swaps (if any) to land covered by the 1995 lease, and had to be a leased swap rather than a sale because the swap had to expire on the same date that the 1995 lease expired. Everything outside that leased area had to remain open space though it could be leased facilities not favouring any single sport. The single exception to that was permission of the East Stand to occupy 1042 square metres in a specific area outside the leased boundary for 9 months of each year with the remaining 3 months being consecutive summer months with the land restored to open space.

Although it is normal for planning permissions to be either permanent or temporary for a specified short period of time, this ruling creates a planning difficulty. It is not possible to grant permanent permissions because the permitted development should not be left in place when the 1995 lease expires, but continuously renewing temporary permissions is contrary to planning guidance.

Go back to top index

The Recreation Ground 2014 Hearing

This was an appeal hearing on 27 March 2014 by the First-Tier Tribunal (Charity) Under the power given in the Charities Act 2011 considering the appeals by three Bath residents against the Trustees being able to consider a land swap for part of the Rec. Unlike the 2002 hearing where the High Court was asked to decide whether the Rec came into council ownership as an acquisition or as charitable land, the Tribunal was asked to rule on whether or not the Charity Commission had the legal right to introduce its Scheme it put forward in June 2013. The Tribunal hearing resulted in an Order dated 24 April 2014 defining a Scheme on how the charity named Bath Recreation Ground Trust would be run. The Objects of the scheme, aside from the financial objectives, states:

The objects of the charity are the provision, with or without charge, of land in or near Bath, including but not limited to the Bath Recreation Ground, for use as outdoor recreational facilities for the benefit of the public at large and in particular for use for games and sports of all kinds, tournaments, fetes, shows, exhibitions, displays, amusements, entertainments or other activities of a like character and the maintenance, equipment or lay out as the trustees shall think fit of such land and always provided that

(i) the charity shall not show any undue preference to or in favour of any particular game or sport or any particular person, club, body or organisation, and

(ii) the charity shall not use the Bath Recreation Ground otherwise than as an open space.

In layman's terms, the Scheme as described by the Tribunal is a bit of a change from the expectations when the land was first conveyed to the (then) council. The words "but not limited to the Bath Recreation Ground" shows that the appeal against the possibility of a land swap was lost. However, the words "always provided that" introduces conditions that are non-negotiable, which includes "the charity shall not use the Bath Recreation Ground otherwise than as an open space". Further down the clauses it is clarified that land swaps are limited to the land covered by the 1995 lease (which is effectively the land currently occupied by Bath Rugby and not the additional land Bath Rugby is exhibiting plans for) and are leased swaps because they cannot exceed the end date of the 1995 lease. There is also an exclusion to the open space requirement for the existing Bath Sports and Leisure Centre with its parking provision, until such time as it ceases to be fit for its current purpose at which point it must be reverted to open space. Thus the building cannot be demolished and replaced with another. One oddity though is that because the 1922 Covenant is replicated in the text of the 1953 Conveyance rather than being appended as a Covenant, the Charity Commission does not have it mentioned as part of the Scheme. The Tribunal was clear that the Charity Commission was allowed to do that, but was equally clear that "this finding does not mean that those covenants and conditions are not enforceable in law. The covenants and conditions are to be interpreted and enforced as a matter of property law. This Decision will have no effect on the enforceability or otherwise of those covenants and conditions as a matter of property law". In layman's terms the 1922 Covenant still exists and is enforceable but it will be the beneficiaries of the Covenant who must pursue it through the courts, not the Charity Commission. The Trustees are required to accompany any variation of the 1995 lease (which cannot have its land area or its expiry date extended) with a Condition that Bath Rugby Club must "minimise disruption to local residents and to users of the charity's land". This takes the 1922 Covenant a bit further, because "disruption" has a wider scope than just building on the Rec and also covers parking problems, litter and anti-social behaviour. Effectively, the subsequent legal clarifications have rendered irrelevant whether the High Court decides the 1922 Covenant should be nullified or retained. The legal proceedings (as clarified by the 2015 hearing above) have also required the Trustees to not allow any structure on the open space of the Rec outside of the 1995 leased area plus the nine-monthly use of a defined additional area for the temporary East Stand.

Bath and North East Somerset Council is identified as the "Custodian Trustee" of the land conveyed to the council in 1956. This is a specific role defined in the Public Trustee Act 1906 that identifies the council as the permanent holder of the Trust land but without the authority to manage it and thus unable to be held liable for the action of the Trustees committing a breach of trust unless the Custodian Trustee has concurred with the breach of trust. Apart from the custodian trustee, there is a requirement (defined in the Operational Guide of the Charity Commission) for one or more managing trustees.

That role goes to the Trustees appointed as part of the Scheme, and at the time of the hearing one of these was a councillor nominated by the council for a fixed term of 3 years, so that expired in 2017. Thereafter, the trustees cannot appoint "members of the council" though one of the should be "nominated by the council". These terms are undefined; though by convention a "member of the council" is an elected person, and thus a councillor. There doesn't seem to be any bar to the person nominated by the council being one of the council's permanent staff. However, no Trustee can serve for more than two 3-year terms.

The Trustees may make rules and regulations for the administration and management of the charity, which must be consistent with the provisions of the existing trusts and this scheme. This requires the Trustees to pursue the objective of the Charity without obligations to pursue the policies or directions of the council or any other body. Also, part of the rules in the Scheme is an obligation that the tenant (ie Bath Rugby) shall make the space they occupy by the 1995 lease available for the uses chosen by the Trustees in a state suitable for leisure purposes for at least 3 consecutive summer months each year. Thus the Charity Commission has endorsed the Condition attached to the temporary permission for the East Stand.

Go back to top index

The Recreation Ground 2013 events

Several news items appeared in the press at this time, all relating to The Rec.

First there was the news of an application for Town Green status. Given that the Recreation Ground was last conveyed in 1956 for the benefit of the citizens of Bath, and because the 1922 covenant was expressly added to the 1956 conveyance of that land forming an unbroken chain of assignments, then the current owner, B&NES, and therefore the Trustees are obliged to both enforce the 1922 covenant and to protect its applicability, and that in 2002 the High Court upheld the conditions of the 1956 conveyance, Mr Sparrow who lives in Bathwick in the neighbourhood of the Rec is entitled by the 1922 covenant to enforce a restriction "that nothing shall be hereafter erected placed built or done upon the said hereditaments and premises ... which may be or grow to be a nuisance annoyance or disturbance or otherwise prejudicially affect the adjoining premises or the neighbourhood". A Public Inquiry into a Town Green must be cheaper for the Trustees to service than another High Court case which would arrive at the same conclusion as the 2002 hearing, and which remains an option if the Town Green application fails. For a Trustee to dismiss this action as "a stalling tactic" simply demonstrates that he has not properly understood his role as Trustee as distinct from councillor, has not studied the legal judgements, and has not complied with the instructions of the Charity Commission: "The Commission directs that ... BANES demonstrate that it has discharged its responsibilities as charity trustee in respect of any decision relating to the current and future uses of the Rec and the resolution of issues arising from the Recís current occupants". Despite this reasonable argument (put forward by 18 supporters), on Friday 15 November 2013, Bath and North East Somerset Council's Regulatory (Access) Committee resolved to refuse the Application to register Bath Recreation Ground as a Town or Village Green pursuant to Section 15 of the Commons Act 2006.

The second Chronicle Item is the news of the Charity Commission consultation. The problem is that the consultation is not a popularity contest, and the size of the majority is irrelevant. The 1922 covenant is binding and it places conditions on a specific piece of land, not any mixture of sites as suggested in the consultation. The Charity Commission will be acutely aware that if they vary the Trust and place it in conflict with the 2002 High Court Judgement, they can be accused of maladministration, or even contempt of court, as indeed can the Trustees. They will also be aware if they study the documentation, that the neighbourhood has a legitimate expectation that the trustees should protect their rights and "no workshops warehouses factories or other buildings for the purpose of any trade or business" is part of that collection of rights. While Bath Rugby was an amateur club, the erection of clubhouse and stands were not forbidden as the amateur club was not a trade or business; but the current privately owned professional club is a business and is excluded from further construction by the covenant. If this is ignored, then each and every household in the vicinity of the Rec can sue for damages if they feel they are, or even could be, prejudicially affected.

The third Chronicle item is a letter from The Bath Society, effectively accusing the council of misleading the public by only advertising that opposition to the Town Green is possible without also informing that support comments for the application is also possible. The sheer scale of 25,000 spectators (Bath Rugby's original target, and probably still the ultimate goal) as described at the end of the letter, is an eye-opener.

We have gone into some detail here to emphasise that although the Rec is held in trust by the council, it is and must remain completely separate from the council's own plans and aspirations. To do otherwise risks significant court costs in the future, and a council already struggling with a tight budget would be acting recklessly if taking any path that could lead back to the High Court. It may not be to their liking, but the council is bound by the signature that was placed on the 1956 conveyance, to which they are successors in title. They should be vociferously trying to enforce the covenant in the manner that the 2002 court ruling interpreted it. So should the Trustees.

Go back to top index

Bath Rugby's 2013 Proposed Development

On 27th and 28th September 2013, Bath Rugby held a public exhibition to show the results of the first thoughts on how the Rec could accommodate 18,000 spectators rather than the current 12,000 capacity. This exhibition was at the concept level, in that it showed where the seating would be, but there were no design proposals showing what the structures holding the seating would look like. In a nutshell the exhibition showed that the South Stand would remain, but alongside it some additional seating is proposed. The temporary East Stand remains. The North Terrace (with its back towards Johnstone Street) and the West Stand (with its back towards the river) would be replaced with new facilities with more seats, and the current Club House is to be demolished and replaced. There was a stated wish to improve how spectators get into and out of the ground, but there were no details of how that was to be achieved.

There were feedback forms at the exhibition and the exhibition material was put on-line with an on-line feedback form. The aim of this exercise was to gauge public opinion and to seek suggestions and ideas about the refinements the public would like to see.

This was followed by a second public exhibition on 15th, 16th and 17th November 2013, with additional information on the exhibition boards including some artist's impressions. It was noted that the capacity was stated to be 16,500 this time.

The greatest help given to visualising what was proposed came in the form of a scale model, showing the development in the context of the surrounding area. This model was not perfect in that the slopes of the land were not able to be properly reflected in the model in the time available to prepare it, but it did allow the appearance of the development to be assessed from a variety of viewpoints. Out photos of the model used here (looking towards the Empire on the left and looking from the Johnson Street direction on the right) are helpful, but are no real substitute for viewing it and walking around it.

The greatest help given to visualising what was proposed came in the form of a scale model, showing the development in the context of the surrounding area. This model was not perfect in that the slopes of the land were not able to be properly reflected in the model in the time available to prepare it, but it did allow the appearance of the development to be assessed from a variety of viewpoints. Out photos of the model used here (looking towards the Empire on the left and looking from the Johnson Street direction on the right) are helpful, but are no real substitute for viewing it and walking around it.

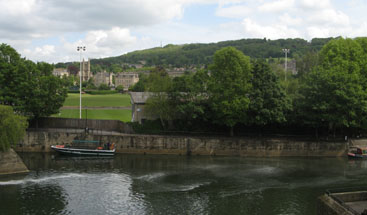

The Chronicle published some of the artist's impressions and we have attempted to match one of the views with a current photograph so that a direct comparison can be made.

The Chronicle published some of the artist's impressions and we have attempted to match one of the views with a current photograph so that a direct comparison can be made.

We were informed that what we were seeing is still work in progress, and there would almost certainly be further alterations as a result of the feedback collected from the visitors to the exhibition and from those who viewed the exhibition material on-line.

Go back to top index

On 12 June 2013 David Dixon, the Chairman of the Recreation Ground Trust, announced that the Charity Commission had agreed the "land swap" by a scheme allowing the Rugby Club to develop the rugby ground on the Rec and that the Trust will have use of land previously used for training by the Rugby Club at Lambridge for charitable use. The Scheme was made by the Charity Commission, and effectively it left the Sports Centre in the control of the council's Trustees and required additional Trustees to manage the remainder of the Rec. and also authorised the Trustees to take on additional land either in addition to or instead of some of the land which forms the Rec as conveyed to the council. It should be noted that at the time that scheme was proposed, "instead of" puts the council as owner in contempt of the Court Judgment of 2002.

At the end of October 2013, the 3-person Board of Trustees who were all Councillors, met to appoint additional Trustees. This follows an agreement by the Charity Commission that the number of Trustees could be increased.

The following now manage the Bath Recreation Ground Trust:

Councillor David Dixon [Cabinet Member for Neighbourhoods] (Chair)

David Durdan [Somerset County Playing Fields Association] (Vice-Chair)

Councillor Tim Ball [Cabinet Member for Homes and Planning]

Don Earley [Fields in Trust]

Stephen Baddeley [Director of Sport, University of Bath]

Elizabeth Bloor [Netball South West & Chair WESPORT]

Derwent Campbell [Mogers solicitors]

Simon Emery [Emerys of Bath Ltd]

Geoffrey Fairclough [Chartered Accountant]

Michael Laughton [Registered Auditor and Chartered Accountant]

These 10 Trustees bring a variety of backgrounds and skills rather than being wholly made up of councillors as the original Board was.

Go back to top index

The Recreation Ground 2011 Consultation

Amid much press speculation about what will happen to The Rec and in the light of a so-called public consultation that failed to ask the right questions and invited contributions from those who are not actually the intended beneficiaries of the transfer of The Rec in Trust to the council, we did our own research. As is common in these cases the further we dug, the more we unearthed. And as news spread that we were digging, things that we might not have discovered for ourselves were brought to our attention. This is how the research evolved.

8th May 2011

Our interest was sparked by the "consultation" of the Recreation Ground, where we expressed our doubts about the true significance of the outcome (hence the quotes around "consultation" above) because the covenant of 1956 transferring the Rec was for the benefit of "the Mayor, Aldermen and Citizens of the city of Bath" and yet nowhere in the questions asked is there a requirement to say whether the respondent falls into any of those categories.

We maintained our view that the consultation document arguing that the Sports Centre breaks the covenant so an extension to the Bath Rugby area can be made acceptable is not a sound position to take. It is rather like saying because a road through Bath has been wrongly marked with a 40mph sign instead of a 30mph sign, by arranging to have the speed camera turned off it would then be acceptable to drive along it at 60mph. Like the arguments being put forward in the Rec consultation document, it is absurd. The legal ruling interpreting the Rec Covenant referred to that specific area of land as conveyed, making any proposals for land swaps ineffective. If the trustees cannot understand that, then arguably they are not fit to be trustees. They should be vociferously trying to enforce the covenant in the manner that the 2002 court ruling interpreted it. That is what trustees are for. Why are they not doing that?

15th May 2011

An Acre = 4840 Sq Yd

A Rood = 1210 Sq Yd

A Perch = 90.75 Sq Yd

Thus the Rec is defined as 80858.25 Sq Yd or thereabouts, thus 67607.8 Sq M, approximately 6.76 Hectare

In the intervening week we informed that there is a second covenant dated 1922 which binds the owner of "All that piece or parcel of ground situate in the City of Bath and containing an area of Sixteen acres two roods and eleven perches or thereabouts and known as The Bath and County Recreation Ground ... " and anybody else the land is subsequently sold, assigned or otherwise transferred to, in perpetuity, to a restriction "that nothing shall be hereafter erected placed built or done upon the said hereditaments and premises ... which may be or grow to be a nuisance annoyance or disturbance or otherwise prejudicially affect the adjoining premises or the neighbourhood". We have also been informed that there are moves afoot to try to revoke this covenant but we have not been able to confirm or deny that by the time this was written.

What this covenant apparently means is that the description used (an area of Sixteen acres etc) removes any possibility of a land swap (whether with the Lambridge site mentioned in the consultation or any other location) being used as a mechanism to get round the restrictions on developing the Rec, and that "the neighbourhood", which the dictionary defines as "the immediate environment" and would normally be interpreted as all buildings closely surrounding the Rec plus any others in line of sight or within earshot, have a legal veto on any development for business purposes that could be (there is no obligation to prove that it will be) a nuisance annoyance or disturbance or prejudicially affect (which would include affecting the property value) themselves or their premises.

It seems unlikely that everybody in "the neighbourhood" will willingly surrender their protection under this covenant; and nowhere in the document is there a suggestion that "the neighbourhood" has to defend its rights (or even know about them) in order to retain them. If any reader regards themselves as being covered by the words "the neighbourhood" and has not been asked for their opinion on surrendering their rights, we suggest that they contact the Trustees of the Recreation Ground (who are the currently assigned guardians) and ask what the Trustees are doing to ensure that the neighbourhood's rights remain in place and can be enforced.

We have seen a copy of the covenant document and have checked that our quotes above are accurate. We will attempt to get the full text of the covenant into a form that can be reproduced on-line so that the quotes can eventually be read in their full context. Meanwhile, if anybody does get a statement from The Trustees and wishes to inform us of what was said, please use the details on our Contact Us page.

29th May 2011

A week later and there are further developments. The Recreation Ground has new Trustees. The Chronicle has announced that Cllrs David Dixon, Tim Ball and Nathan Hartley have taken over from Cllrs Chris Watt, David Hawkins and Vic Pritchard, the trustees under the previous administration. We were also contacted to say that some letters had been received about plans for the Rec, and asked if we wanted to see them (which of course we did).

We were shown two pieces of correspondence, one on Bath Rugby headed paper and the other on paper carrying the name of a local solicitors practice. Both are similarly worded, and try to pretend that the people who benefit from the 1922 covenant need to have had the benefit expressly conveyed in any sale since 1922. It also claims that anybody attempting to retain the protection of the 1922 covenant would be a defendant, and by implication liable to costs if the defendant loses.

Protective Costs Order

It is UK (and EU) policy that if a case should be heard in the public interest, the public should not be deterred from lodging the case by the fear of having to meet all the costs if the case is lost. A judge can grant grant a Protected Costs Order which limits the exposure to costs if the case is lost (if the case is won, the costs are met by the other side).

These letters look like an attempt to browbeat the opposition with false claims. Any individual taking court action to protect the covenanted rights of the neighbourhood would have an obvious claim to be acting in the public interest and so should automatically qualify for a Protective Costs Order (see box, right), leaving Bath Rugby to bear all their own legal costs even if they win. However, they are not likely to win:

Firstly, the covenant is not attached directly to the surrounding properties as the correspondence suggests, it is attached to the land known as the Recreation Ground. The Recreation Ground was last conveyed in 1956 for the benefit of the citizens of Bath, and because the 1922 covenant was expressly added to the 1956 conveyance of that land forming an unbroken chain of assignments, then the current owner, B&NES, and therefore the Trustees are obliged to both enforce the 1922 covenant and to protect its applicability:

"The Purchasers for themselves their successors and assigns hereby covenant with the Vendor his successors in title and assigns and to the intent and so that this covenant shall run with and be binding on such portions of the hereditaments and premises hereby conveyed as are respectively affected thereby into whosoever hands the same may come ..."

A 2002 High Court judgement (BATH AND NORTH EAST SOMERSET COUNCIL v HM ATTORNEY GENERAL)

clarified the status of the Recreation Ground, so the current situation has recently been tested in a court, and that case will have tested claims and counterclaims against all relevant legislation prior to that date. The text of that judgement is evidence that the court recognised the existence and relevance of the 1922 covenant. The threatened Declaration is to claim that the covenant is unenforceable, but The Recreation Ground Trust, Bath is able, and duty bound, to enforce it. It only requires them to refuse permission for unpermitted buildings. The ability to enforce was evaluated in the 2002 court judgement, and that must be taken into account in any future proceedings. However that judgement made no ruling regarding the current use of the Rec: "That conclusion in no way pre-empts the question whether the actual uses to which the claimant has put the Recreation Ground, in particular the most recent letting of the football ground, are compatible with the charitable trusts. That is a question which this judgment does not seek to answer." The existing use cannot therefore claim any legitimacy from this judgement.

Secondly, the surrounding premises who wish to protect their rights under the covenant are witnesses not defendants, because their premises are "the neighbourhood" which is protected by the conveyance, and not part of the conveyed land. The neighbourhood has a legitimate expectation that the trustees should protect their rights and "no workshops warehouses factories or other buildings for the purpose of any trade or business" is part of that collection of rights. While Bath Rugby was an amateur club, the erection of clubhouse and stands were not forbidden as part of a business; but a privately owned professional club is a business and is excluded from further construction by the covenant. If the Council or its Trustees does not oppose the Declaration, then each and every household in the neighbourhood is entitled to claim damages from them for maladministration if the rights given them in the 1922 covenant are not used and any subsequent development for business purposes which the Trustees do not oppose creates "a nuisance annoyance or disturbance or otherwise prejudicially affect the adjoining premises or the neighbourhood".

Thirdly, the correspondence we saw claims that the council have raised no objection. But of course that was when the former Trustees were in office, and probably they were not made aware of the possible penalties for inaction.

It is likely that the new Trustees, if they are made aware of the risks they run (as outlined above) should they raise no objection, might take a different view. They should also bear in mind that the Charity Commission has only reviewed the presence of Bath Rugby in the context of the 1956 covenant, because the 1922 covenant was not mentioned in that paperwork and yet even so that review resulted in a directive from the Charity Commission which is still extant: "The Commission directs that ... BANES demonstrate that it has discharged its responsibilities as charity trustee in respect of any decision relating to the current and future uses of the Rec and the resolution of issues arising from the Recís current occupants and that such decision was properly taken by BANES in the best interests of the Charity". Council Tax payers must hope that they do make responsible decisions. The risk of numerous damages claims from "the neighbourhood" (probably each covered by a Protective Costs Order) cannot possibly be in the best interests of the charity, regardless of how beneficial they regard Bath Rugby as a tenant, particularly when the council's annual financial statement admits "The Council as Trustee is ultimately responsible for any liabilities or deficits incurred by the Trust".

The new Trustees appear to have inherited a real hot potato, thanks to the failure of the outgoing Trustees to operate the charity independently of the interests of others. It is an unfortunate fact of life for Bath Rugby that although they can't be arbitrarily removed from that part of the Rec for which they have a lease and they would not have been in their current position regarding additional facilities on the Rec if they had remained an amateur club, nevertheless such sentiments do not override the council's need to now administer the charity in the way that the High Court ruled that it should be administered. Our expectation, from our researches to date, is that neither the courts nor the Charity Commission are likely to support the Council and its Trustees if they take any action other than opposing the aspirations of Bath Rugby on the heavily covenanted Recreation Ground. The Charity Commission has ordered B&NES to (among other things) "act in good faith", and to do that the Trustees must remember that the beneficiaries of the Trust are "the Mayor, Aldermen and Citizens of the city of Bath" and those covered by the description "the adjoining premises or the neighbourhood" of the Recreation Ground, and not Bath Rugby or its supporters from other parts of the country.

Legal Clarification

Prior to 1956, the Recreation Ground was owned and managed by the Bath and County Recreation Ground Company Limited who had acquired it on 6 April 1922 from William Foster subject to specific covenants and conditions (subsequently referred to as the 1922 Covenant). On 1 February 1956 it was transferred to "The Mayor Aldermen and Citizens of Bath" for an agreed some of money subject to some specific conditions, "TO HOLD the same unto the Corporation in fee simple upon trust that the Corporation for ever hereafter shall manage let or allow the use with or without charge of the whole or any part or parts of the property hereby conveyed for the purpose of or in connection with games and sports of all kinds tournaments fetes shows exhibitions displays amusements entertainments or other activities of a like character and for no other purpose and shall maintain equip or lay out the same for or in connection with the purposes aforesaid as they shall think fit but so nevertheless that the Corporation shall not use the property hereby conveyed otherwise than as an open space and shall so manage let or allow the use of the property for the purposes aforesaid as shall secure its use principally for or in connection with the carrying on of games and sports of all kinds and shall not show any undue preference to or in favour of any particular game or sport or any particular person club body or organisation." The 1956 Conveyance also required the 1922 Covenant to be upheld: "That the Corporation will observe and perform the covenants and conditions contained in the said conveyance to the Company dated the 6th day of April 1922 so far as the same are still subsisting and capable of being enforced". This was partly to give recognition to the fact that in 1956 there was an extant lease of part of the land to Bath Football Club which still had 27 years left to run.

The statement "The Corporation for ever" ensured that it transferred to the Local Government identity responsible for Bath from time to time from Bath City Council in 1972 via several intermediaries to Bath and North East Somerset in 1995. B&NES treated it as land usable for recreation purposes (under a piece of legislation in 1937) rather than observing the stated obligation to retain it as an open space, and part of the land was used for a Sports Centre with car parking beneath. B&NES also replaced the expiring lease with a 75-year lease dated 23rd May 1995, granted to The Trustees of the Bath Football Club, of about 14,907 sq. m. of the Recreation Ground (referred to in court papers as "the 1995 Lease"). At that time the Bath Football Club was an amateur Rugby Union club and amateur clubs were allowable under the 1922 Covenant. However in 1995 the amateur club became a professional organisation known as Bath Rugby and it had a private owner, yet a professional business was not acceptable under the 1922 Covenant, and this cast doubts about the ongoing validity of the lease. In 2013 Bath Rugby accepted at a Tribunal Hearing into a proposed modification of the charity scheme that "the use of the Recreation Ground for elite rugby was not within the objects of the Charity and that the advancement of professional sport is not a recognised purpose in charity law" but the Hearing concluded it was to examine the legality of the amendments to the scheme which the Charity Commission was proposing and the validity or not of a lease was not relevant to that activity.

The Stadium

The new stadium was first put forward in 2000. This created a lot of opposition, including opinion from a retired Planning Inspector who pointed out that there were a number of planning reasons why it would have failed on appeal if ever entered the appeal processes, and a retired barrister who pointed out that the council inherited conditions alongside the ownership of the Rec and they were thus unable to legally grant permissions which the conditions made unacceptable.

The arguments in the press escalated and polarised with the rugby supporters vociferously in favour and those who thought the rugby club should not be allowed top operate outside the law under which the council as owner was required to operate, and the council itself which insisted that it was able to define policy for all the assets it owns. Eventually, to settle the issue the council asked the High Court to clarify the status of the Rec. In 2002 the Chancery Division of the High Court (as Case Reference [2002] EWHC 1623 (Ch) it reached its conclusion. The court was "persuaded that the public character of the Corporation and the fact that it was intended to be the trustee in perpetuity enables one to conclude that the dominant intention of the trusts, to which all the express provisions should be regarded as ancillary, was to provide a recreational facility for the public, and that, construed as such, the trusts are valid charitable trusts". The court recognised the council as Trustee of the charity. In November 2002 the Charity Commission recognised the Charitable Trust, and the initial Scheme reflected the 1956 Conveyance, though the Charity Commission began an internal investigation into what the eventual Scheme should be.

The initial finding was that after the 2011 reshuffle (described above) which replaced three councillors with three other councillors, Council should not control the selection of Trustees because of a potential conflict of interests between the charity and council policies, and a new set of Trustees was elected. This was further complicated by the planning policy first drafted in 2011 and eventually embedded in the Approved Core Strategy in 2016 which expressly permitted development of a stadium on the Rec"subject to resolution of any unique legal issues and constraints".

Go back to top index