University of Notre Dame School of Architecture

Quick Finder (Follow links for more information)

| Western Riverside, 2009 | Kingsmead, 2011 |

| Initial Contact | Background |

| Traditional Architecture | March Colloquium |

| Urban Design | May Presentation |

| Outcome | |

| Manvers Street, 2013 | Narrow Quay, 2015 |

| May 28th Presentation | May 22nd Presentation |

Narrow Quay, 2015

The May 2015 Presentation

It was the intention that a professor and a group of students should visit Bath and mount a presentation of their work back in the University of Notre Dame, but a week before they were due to travel the funding for the students was reallocated, and it was the Professor from Notre Dame and a Doctor from Judson University (a former student of the Professor) who came to Bath with the Notre Dame student's work, which was put on display alongside an extract from the Doctor's Masters Thesis dealing with the Walcot Street Cattle Market area.

It was the intention that a professor and a group of students should visit Bath and mount a presentation of their work back in the University of Notre Dame, but a week before they were due to travel the funding for the students was reallocated, and it was the Professor from Notre Dame and a Doctor from Judson University (a former student of the Professor) who came to Bath with the Notre Dame student's work, which was put on display alongside an extract from the Doctor's Masters Thesis dealing with the Walcot Street Cattle Market area.

The start of the presentation was by Professor Economakis, who took a look back in history, showing that Bath grew in a cellular fashion adding neighbourhoods, and identified the urban principles underpinning a viable neighbourhood. It also looked at sustainability, and the contribution that neighbourhood layout, content and building design each make towards it. A quick look back at the student designs for Western Riverside, Kingsmead and Manvers Street showed how these principles were incorporated into those schemes. Sustainability was to be examined in more scientific detail by Dr. Miller later.

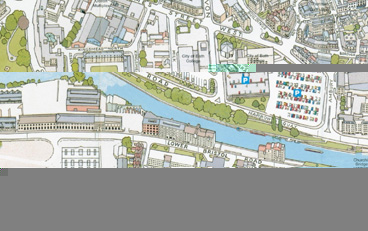

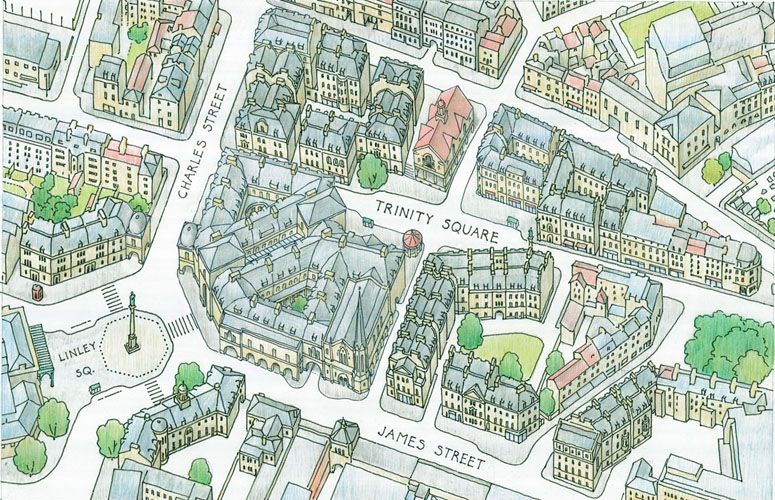

The student project for 2015 was then presented. It was based on an area within the boundary of this map. Students had also researched old maps, and had concluded that the now missing Back Street and Little Corn Street, destroyed for the construction of the Avon Street car park, provided some useful permeability. Also the public space that was Kingsmead Square deserved a similar public space at the other end of Avon Street, and this was named Herschel Square on the students' urban design.

The student project for 2015 was then presented. It was based on an area within the boundary of this map. Students had also researched old maps, and had concluded that the now missing Back Street and Little Corn Street, destroyed for the construction of the Avon Street car park, provided some useful permeability. Also the public space that was Kingsmead Square deserved a similar public space at the other end of Avon Street, and this was named Herschel Square on the students' urban design.

Because this was a student exercise rather than anything specifically needed by Bath, they were required to design a public building as well as housing, office space and shops; and this took the form of a museum. Each student made their own design for a museum occupying a particular given land area, but jointly they decided it should be a Museum of Science and Industry, to complement the industrial buildings on the opposite bank of the river. They were also given expectations of longevity, that what they designed should last at least two centuries. The designs varied and it would be wrong to single out some and omit others and space does not permit all to be shown here, but for those interested we have put the presentation slides together as a document which can be viewed from this link. This contains 21 graphical slides so will take some time to download, and some patience will be necessary.

Manvers Street, 2013

The May 2013 Presentation

A professor and eleven students came to Bath, and mounted the presentation of their work back in the University of Notre Dame between two busy days of study and sightseeing. One of the students provided us with a copy of his photos, including this group photo, taken in Prior Park.

A professor and eleven students came to Bath, and mounted the presentation of their work back in the University of Notre Dame between two busy days of study and sightseeing. One of the students provided us with a copy of his photos, including this group photo, taken in Prior Park.

Their urban design exercise started with an assumption that the Police Station and the Post Office Sorting Offices would want to relocate at some time in the future and the more recent office buildings would remain initially but eventually reach the end of their lifespan and be replaced, allowing the site to be redeveloped in phases around the heritage assets which would remain.

The presentation was to an invited audience of Council officials, Councillors, Council Officers, representatives of several organisations interested in heritage or World Heritage, some architects and architectural advisers, and various others who had a professional interest in Bath. In total, the audience numbered about 40 people.

The Chairman of the Council and the Council Leader both gave a welcome address and after the presentations and questions, a closing address. The presentation was well received.

The theme of the presentation was two-fold. The overall site layout was intended to be a welcome to Bath for those arriving by train, plus a space where visitor accommodation, permanent residences, places of employment, places of relaxation and places for retail businesses all mixed with open spaces, views through sight lines, and river facilities. The buildings were all intended to be sustainable in that they were designed for longevity, constructed with an expected life of several centuries, and adaptable so that during that long life their use could be altered, for instance being converted both ways between places of business and living accommodation as needs change.

In the (hand drawn) drawing above, the road at the top is Manvers Street which actually runs north/south but for this web page we have turned it sideways to better fit on a PC screen. The road to the right is South Parade, which the students have helpfully continued onto a pedestrian bridge to connect to the riverside path and the Cricket Club ground. The treasured buildings (The Royal Hotel, Bayntun's, the Baptist Church, the mini-cab office, and St John's church) are retained, as is the underground parking, though now roofed over for a hotel and a public park to be located above. We were told that there is a similar arrangement in Chicago which works well. The immediate riverside area is a pedestrian precinct with landing places for pleasure craft. The spike or obelisk on the far river bank marks the exact centre of John Wood's "Royal Forum" scheme which South Parade began but the remainder was never completed

Some of the blocks were given to more that one student for each of them to prepare detailed drawings; and a range of elevational treatments were shown to demonstrate that there is no single definitive answer to what a building should look like.

We are hoping to obtain more of the exhibition material later, at which time we will add to this section. Meanwhile, the author of the Virtual Museum of Bath has placed his article on-line and it includes some additional background and pictures.

Go back to top index

Kingsmead, 2011

Classroom Exercise 2011

Following the success of the 2009 Summer School which focused on the Western Riverside (see below), the University has been in touch with Watchdog requesting some background information on the Kingsmead area.

Rather than have students visit Bath for their project as they did in 2009, this time the intention is to explore the possibilities for the sites in the Kingsmead area listed in the council's Core Strategy as a whole term (they call it semester) class exercise. Watchdog has been asked to provide historical background, maps, photographs and relevant regulations (eg PPS25 etc) to give a feel for the area and what is possible, along the lines of what the Summer School of 2009 was able to see for themselves by being in Bath.

This is an educational experiment, being the first time the students have tackled an overseas project without being on site, and Watchdog is delighted to have been trusted with the on-location support.

The project will begin on 18th January 2011, and the University has expressed a desire to visit Bath to present the students' work during May if it can be arranged.

The March 2011 Colloquium

At the end of March, Watchdog sent a representative to the University of Notre Dame in Indiana in response to an invitation to take part in a colloquium entitled "Modernity, Social Change and Tradition in Historic Bath". This event had been timed to allow the participants to also attend the 2011 award ceremony for the $200,000 Richard H. Driehaus Prize for Classical Architecture which was established and is presented annually through the University of Notre Dame School of Architecture to honour a major contributor in the field of traditional and classical architecture.

Alongside Watchdog at the colloquium were others from Bath: Caroline Kay, the Chief Executive of the Bath Preservation Trust; Stephen Green, a Director of Future Heritage Group, a Bath company specialising in the restoration of historic buildings; and Timothy Richards, a Director of a Bath based architectural artist and sculptor's business. From outside Bath came Professor David Watkins, the Professor Emeritus of History of Architecture from Cambridge University, plus Bradford Houston, a Salt Lake City based architect working for a world-wide organisation, and finally Thomas Rajkovich, the Principal of an architectural company in Evanston, Illinois. These last two were former graduates of Notre Dame University.

Alongside Watchdog at the colloquium were others from Bath: Caroline Kay, the Chief Executive of the Bath Preservation Trust; Stephen Green, a Director of Future Heritage Group, a Bath company specialising in the restoration of historic buildings; and Timothy Richards, a Director of a Bath based architectural artist and sculptor's business. From outside Bath came Professor David Watkins, the Professor Emeritus of History of Architecture from Cambridge University, plus Bradford Houston, a Salt Lake City based architect working for a world-wide organisation, and finally Thomas Rajkovich, the Principal of an architectural company in Evanston, Illinois. These last two were former graduates of Notre Dame University.

The students had been working jointly on a long term mixed use masterplan for the Kingsmead area, on the assumption that the sites of Kingsmead House and Plymouth House would become available first, but eventually the Rosewell Court buildings would life expire and something would be needed to replace them.

They also were working separately on a common project. Having identified in the masterplan a location for a Museum of Bath (somewhat arbitrarily sized to house the Building of Bath exhibits, the council exhibits in St John's School and the Victoria Art Gallery stored because there is no available display space), the Bath Blitz exhibits, plus display space for information on the wool trade, medieval Bath, and Victorian Bath. Each student created his or her own arrangement of exhibition spaces and administration spaces within a common plan form of boundary and supporting walls.

Within the masterplan, different groups of buildings were allocated to each student, who would then design the elevations, the internal spaces and partition walls and the fenestration.

All the drawings which were presented were hand drawn and hand coloured in watercolour so there are no electronic images of them that can be reproduced here. However we did manage to capture some of the projected images used during the colloquium. These are nowhere near the quality of the originals, but do serve to convey the concepts.

All the drawings which were presented were hand drawn and hand coloured in watercolour so there are no electronic images of them that can be reproduced here. However we did manage to capture some of the projected images used during the colloquium. These are nowhere near the quality of the originals, but do serve to convey the concepts.

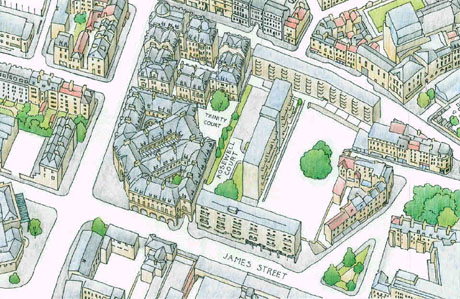

The first notable concept is that rather than a curved facade around the Charles Street and James Street West corner, the students have chosen an angled approach, presenting a flat face roughly parallel to the front of Green Park Station. This facade contains a pedimented arch giving access to a passage through to the square behind which has shops on either side with flats above along the style of The Corridor. This is the first phase of the masterplan which assumes that only the Kingsmead House and Plymouth House land can be used. The existing access road behind Rosewell Court has been retained, but now it serves a dual purpose, also giving access to an underground car park beneath the new development.

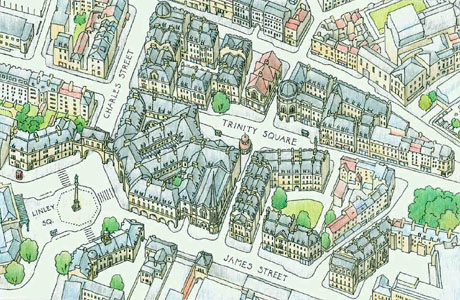

The end-stage diagram of the masterplan is much more radical. The 1960s buildings that make up Rosewell Court are now replaced, restoring the line of Kingsmead Street that existed pre-war. The new residential dwellings provide roughly the same number of units as the buildings demolished.

The end-stage diagram of the masterplan is much more radical. The 1960s buildings that make up Rosewell Court are now replaced, restoring the line of Kingsmead Street that existed pre-war. The new residential dwellings provide roughly the same number of units as the buildings demolished.

There are several things to note in this picture. On the floor plans, a space labelled "auditorium" which could be a concert hall or conference facilities, has been decorated on the outside in the style of the war damaged Trinity Church as a visually unobtrusive way of hiding the true scale of such a large building. A Market Cross style building provides an "open air but under cover" cafe space below open plan office accommodation. The octagonal domed building could be a multi-storey Department Store, positioned to be the end of the sight line through the new Corridor. Trinity Square was suggested as an "access only" space, pedestrianised apart from delivery vehicles serving the shops and offices.

The remaining obvious changes are perfectly acceptable as part of a classroom exercise though they are likely to be controversial in real life. The west side of Charles Street is dismantled and rebuilt with an angled centre, and the Salvation Army Citadel is rebuilt on the same site with the same internal floor area but also angled to give a four sided square (named after Thomas Linley, the famous musician from Bath).

The remaining obvious changes are perfectly acceptable as part of a classroom exercise though they are likely to be controversial in real life. The west side of Charles Street is dismantled and rebuilt with an angled centre, and the Salvation Army Citadel is rebuilt on the same site with the same internal floor area but also angled to give a four sided square (named after Thomas Linley, the famous musician from Bath).

The sketch on the right is difficult to see on-screen, but it does show the through routes from Green Park Station via Trinity Square to Monmouth Street, and (perhaps at a higher resolution) the different buildings used for retail, office and residential.

This is all work in progress. Following the feedback given at the colloquium, there will almost certainly be changes to these designs. However, the ideas were worth bringing to Bath's attention, which is why they are reproduced here.

Go back to top index

The May 2011 Presentations

Professor Richard Economakis and the students of the School of Architecture from Notre Dame University in Indiana presented their ideas for redeveloping the Kingsmead area of Bath in three well-attended sessions spread over the last two days in May in two of Bath's iconic historic buildings.

Professor Richard Economakis and the students of the School of Architecture from Notre Dame University in Indiana presented their ideas for redeveloping the Kingsmead area of Bath in three well-attended sessions spread over the last two days in May in two of Bath's iconic historic buildings.

The first session was attended by the Mayor of Bath, Cllr Shaun McGall, and the Vice-Chairman and Mayor elect, Cllr Bryan Chalker, pictured here discussing what they had seen with the students who designed it. The professor and students also met separately with councillors and council officers to explain the rationale behind their designs. This was a private session to which Watchdog was not invited, so we cannot report on it.

It must be remembered that what was presented is a student exercise, so it included structures which the students had to learn to design which might not fit in with Bath's aspirations for the area. Nevertheless, the students will be tomorrow's practising architects and masterplan designers, and apart from the odd exercise driven quirk, the overall impression should be that the presentation showed a fitting design for the Kingsmead area of Bath. The consensus of the audiences was that it did.

It must be remembered that what was presented is a student exercise, so it included structures which the students had to learn to design which might not fit in with Bath's aspirations for the area. Nevertheless, the students will be tomorrow's practising architects and masterplan designers, and apart from the odd exercise driven quirk, the overall impression should be that the presentation showed a fitting design for the Kingsmead area of Bath. The consensus of the audiences was that it did.

The primary theme of their presentations this time was "Sustainability". Two aspects were examined: durability and materials. These two are linked in that it takes a lot more energy to manufacture steel, glass and cement than it does to quarry and cut stone or to make bricks; and yet buildings constructed of steel, glass and cement have a shorter lifespan and higher embodied carbon footprint than traditional stone or brick buildings.

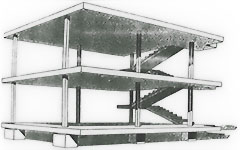

To illustrate durability, the comparison was made between the traditional approach of a building constructed of stone (pictured immediate right) where the walls are load-bearing and most of the stability of the structure is due to gravity. By contrast, a typical concrete and steel building consists of a framework to which the outside walls are fixed (picture far right) and the effect of gravity is to put shear stresses on the fixings. Eventually the fixings weaken and the building has reached the end of its safe life. Typically this will be a 30-50 year life compared with the 300-500 year life of a traditional building.

To illustrate durability, the comparison was made between the traditional approach of a building constructed of stone (pictured immediate right) where the walls are load-bearing and most of the stability of the structure is due to gravity. By contrast, a typical concrete and steel building consists of a framework to which the outside walls are fixed (picture far right) and the effect of gravity is to put shear stresses on the fixings. Eventually the fixings weaken and the building has reached the end of its safe life. Typically this will be a 30-50 year life compared with the 300-500 year life of a traditional building.

A picture is worth a thousand words. This view of the new extension on the Holburne shows the original stone-built "Sydney Hotel", already 200 years old and likely to last at least as long again, seen beyond its ceramic clad extension which will probably need to be replaced four times in that timescale. Environmentally friendly it is not. No amount of so-called sustainability features will offset the huge carbon footprint embodied in the materials and construction in such a short lifetime.

A picture is worth a thousand words. This view of the new extension on the Holburne shows the original stone-built "Sydney Hotel", already 200 years old and likely to last at least as long again, seen beyond its ceramic clad extension which will probably need to be replaced four times in that timescale. Environmentally friendly it is not. No amount of so-called sustainability features will offset the huge carbon footprint embodied in the materials and construction in such a short lifetime.

The next theme was about style. Whilst a steel and concrete building can be virtually any shape and size, traditional buildings with load-bearing walls have practical limitations on the height that can be economically achieved.

They also have a limit to how many holes can be inserted in the form of windows or doors. The outcome is a style of building that is not specifically Georgian or Victorian or Edwardian, but which has similar proportions to those styles and would fit well with the existing character of Bath. Apart from the "monumental" buildings like The Circus, most of Bath's historic buildings are fairly plain (see picture right), and it is mostly the detailing round doors and parapets that distinguish them.

They also have a limit to how many holes can be inserted in the form of windows or doors. The outcome is a style of building that is not specifically Georgian or Victorian or Edwardian, but which has similar proportions to those styles and would fit well with the existing character of Bath. Apart from the "monumental" buildings like The Circus, most of Bath's historic buildings are fairly plain (see picture right), and it is mostly the detailing round doors and parapets that distinguish them.

Thus any traditionally built edifice with load bearing walls will look as though it belongs to Bath if it is constructed from appropriate materials, and by varying the detailing it can take on a character of its own or blend in with the local style.

Thus any traditionally built edifice with load bearing walls will look as though it belongs to Bath if it is constructed from appropriate materials, and by varying the detailing it can take on a character of its own or blend in with the local style.

The picture on the left is an extract from one of the student drawings, showing shops, offices dwellings and a museum entrance; and while it is not a replica of anything currently in Bath it would not look out of place in the Charles Street and Monmouth Street area.

The picture on the right is another extract, for a different position in the street. Again it has its own character rather than being a copy of anything that currently exists and it demonstrates the way different detailing for shop fronts, doors and windows gives it distinguishing characteristics, whilst the underlying proportions of stone to windows and doors, largely dictated by the need to have the building self-supporting under the influence of gravity for several centuries, remains very similar.

The picture on the right is another extract, for a different position in the street. Again it has its own character rather than being a copy of anything that currently exists and it demonstrates the way different detailing for shop fronts, doors and windows gives it distinguishing characteristics, whilst the underlying proportions of stone to windows and doors, largely dictated by the need to have the building self-supporting under the influence of gravity for several centuries, remains very similar.

The next theme was to create an area which people would want to use. This involves having roads and footpaths where people will want to go, and a design that has a mix of residences, shopping, leisure destinations and jobs. The masterplan adds extra through routes for pedestrians to the reinstated pre-war routes of Kingsmead Street and Cross Lane. It also retains and slightly extends the underground parking that already exists beneath the Plymouth House and Kingsmead House sites. The first phase replacing Kingsmead House and Plymouth house but retaining Rosewell Court, remained very similar to the drawings seen in March (and pictured in the March section above).

The final phase masterplan showed some differences from the outline seen in March, because the feedback at that session had provoked some modifications

All the existing buildings apart from Kingsmead House, Plymouth House and the Rosewell Court area flats have been retained, though in order to create Linley Square as a traffic calming measure, it would be necessary to reassemble the Charles Street offices building and the Salvation Army Citadel to turn the corners There are some quirky disguises too. The community hall has had its large size concealed by being given the outside appearance of a church, and the market cross hides the lifts and stairs to the underground car park.

As a masterplan it has all the necessary through routes, a reasonable amount of public open space, some of it green space, and adaptable buildings to accommodate any combination of mixed use in years to come. It has a common underlying style in human scale, which lends itself to becoming a neighbourhood where people feel comfortably at home, and where dwellings can be bought that will last long enough for them to be passed down the generations.

As a masterplan it has all the necessary through routes, a reasonable amount of public open space, some of it green space, and adaptable buildings to accommodate any combination of mixed use in years to come. It has a common underlying style in human scale, which lends itself to becoming a neighbourhood where people feel comfortably at home, and where dwellings can be bought that will last long enough for them to be passed down the generations.

When this masterplan is compared with a mix of scales and styles like in the Southgate area, where the new buildings overpower the older properties yet have a shorter life, the benefits of the students' approach, of creating somewhere to belong, is obvious.

Adaptability was the final theme introduced. If a building is to last a long time, then it must be adaptable to changing needs over time. Thus their building units are designed to be able to change from offices to houses to shops to flats to guest houses to workshops, all of varying sizes, by choosing a versatile but relatively small unit that can be subdivided into smaller ones or combined with neighbouring units to make larger premises. This is achieved by designing buildings strong enough to accommodate openings between units if there is a need to extend horizontally, by including sufficient staircases in the best position to subdivide units vertically, but which could be replaced by escalators if there is a need to make a shop extend over several floors. Similarly, each unit has a space that can be made into a lift, giving the disabled, the elderly and and the infirm the opportunity to live or work on the upper floors.

Although Bath already has more than enough motor vehicles using its streets, it is nevertheless necessary to provide parking. Office accommodation without parking for senior managers and their visitors is almost impossible to let, and shops with a parking space for customers loading their purchases are likely to be more viable. Places of work need some parking spaces for disabled employees and dwellings should not exclude residents of limited mobility who rely on a car for even short journeys. The design is quite right to provide parking; how it is used and by whom then becomes a matter of policy.

Each presentation ended in a lively and thought provoking question and answer session, and the students learned a lot from it. Like the School of Architecture's previous design for Bath (the presentation of a scheme for the Western Riverside in 2009) this year's design received popular though not completely unanimous support.

Another part of the world showed Bath what it would like to see in the World Heritage City, and Bath liked what it saw.

Go back to top index

Summer Studio in Bath 2009

This is the text of the information notice we received (we have retained the American spelling).

This three week program in Bath offers an opportunity for architecture students to familiarize themselves with one of the most significant historical cities in Britain. Bath is renowned for its Georgian buildings, where the influence of the Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio is especially felt. It is also known for the great sweeping Crescent and Circus that were laid out by the architect John Wood the Elder, which represent a new picturesque approach to the conception of urban spaces. Less is known about the sensitive interventions at the center of the city by contemporaries of Wood like Thomas Baldwin, John Eveleigh, John Palmer and others, or even the evolution of the Georgian townhouse and other building types that were emerging at the time, and which reached maturity in Bath.

In the first week, the team will explore the Bath's Georgian architecture and urbanism, with a focus on building and spatial types, and urban block morphology. The city will also be studied for the impact of modernization. In a focused academic exercise, students will apply the lessons learned and produce urban proposals that respect the city’s classical and traditional character. The results of the design effort will be discussed in an open forum on June 8th.

Open Forum Venue; Salvation Army Hall, Opposite - Bath Green Park Station,

6pm for 6:30.

Ongoing sketches may be seen at Timothy Richards Architectural model making workshop - behind St Marks Church or bottom of Holloway Hill. Week beginning 1st - Sunday 7th June inclusive.

Traditional Architecture

A dozen years ago the curriculum and the courses' content were reformed to focus on traditional and classical architecture and urbanism. It is worthwhile to reflect for a moment about what those four words mean.

A dozen years ago the curriculum and the courses' content were reformed to focus on traditional and classical architecture and urbanism. It is worthwhile to reflect for a moment about what those four words mean.

Classical architecture is the best that a tradition produces. Every culture has a tradition. Ours runs from ancient Greece and Rome through the founding of the United States (think of Jefferson's wonderful buildings) and on into the present.

Urbanism is the counterpart to architecture. In training our students to be leaders in the profession of architecture, we must equip them to build and improve our cities and rural areas. In a well-designed, livable city, the public realm complements the private realm, and not all buildings are classical. Indeed, most are good traditional buildings contributing to a complementary public realm (think of Rome). We therefore teach our students how to work with the appropriate national, regional, and local traditions of urbanism, architecture, and construction. What works in America won't necessarily do well in Panama. What is right for Boston is not right for Phoenix.

Rejecting tradition or launching a radical transformation at its expense as occurs in most other schools of architecture ill equips a person to use his or her God-given gifts to make the built world a better place for everyone. Such an education deprives a person of the inexhaustible fund of experience tradition makes available for guiding leaders. Tradition is much broader than classicism. Classicism is only the narrowest, highest peak of achievement standing out above the broad plain of tradition, an inspirational example of the best to be sure, but an isolated peak nonetheless. No plain, no peak. We can live on the plain, but a peak is a rather narrow roost.

Go back to top index

Urban Design

On 5th June, Watchdog was among the invited guests to a presentation and subsequent discussion on urban design. This was world wide in scope, covering pictorial examples in Italy, Greece, Germany America and for the British audience, England and Scotland.

The notes we took of the presentation by Richard Economakis, Assoc. Prof., University of Notre Dame included some basic principles for comfortable living, and some guidelines to ensure sustainability. We have summarised these below (and have anglicised the spelling).

NEW URBAN PRINCIPLES

- The traditional city comprises neighbourhoods, districts, and corridors

-Neighbourhoods are compact, mixed use, walkable areas

-Districts are single-use areas (e.g. medical, athletic, industrial, etc.) requiring separation from neighbourhoods

-Corridors are thoroughfares that channel heavy vehicular traffic safely between and around neighbourhoods and districts - The traditional city expands incrementally, by neighbourhoods

- Neighbourhoods are never larger than 10 or 15 min. walk from one end to the other

- Neighbourhoods have clear centres (public gathering spaces) and boundaries

- Civic buildings are concentrated near the centres of neighbourhoods, around open public spaces or along broad streets

- Civic and commercial functions are situated on the ground levels of buildings

- Heavy retail and noisy or otherwise disruptive functions (e.g. hospitals, schools, etc.) are concentrated on the periphery, along corridors

- Buildings are generally no taller than four to six storeys in height, for maximum unassisted access

- Within neighbourhoods, vehicular traffic is channelled along designated, controlled streets

- Parking is located as much as possible within urban blocks and garages, and along streets

SUSTAINABILITY

Traditional cities and buildings:

- Avoid occupying arable or pastoral land

- Make use of natural, locally available materials (low embodied energy)

- Rely on natural load-bearing building techniques (low embodied energy)

- Are built to endure over many generations

- Are conceived to permit adaptive reuse

- Incorporate parks, gardens and trees, and generally respect natural features in the landscape

- Make use of passive energy systems

- Easily accommodate useful new technologies (solar panels, etc.)

- Are designed to encourage pedestrian links and accessibility (compact, mixed use neighbourhoods)

Afterwards

It was interesting to examine how these principles have been applied in the past. Take the neighbourhoods of Twerton and Oldfield Park. Twerton is older, a woollen manufacturing place that was compact and walkable, with its own High Street shops along its main corridor (it was the main road to Bristol until Brunel brought the railway and moved the Lower Bristol road), an industrial district (Carrs Mill) and open space for people to meet (Twerton Park). With growth following the coming of the railways, East Twerton was formed, with the Moorland Road shopping centre, its own industrial district (the Gas Works and the Marshalling Yards), bounded by the S&D Railway line with its public meeting space inside The Triangle. The 10-15 minute walk took you part way into what is now called Oldfield Park bounded by Wells Road. Rather than an industrial presence, its district is educational, with both the areas now occupied by Hayesfield School having been set aside for educational purposes long ago. The next neighbourhood centres on Bear Flat with its shops, with Alexandra Park as its open space, and (at the time) Holloway and Wellsway being its main corridor. Lower Weston and Westmoreland and Widcombe also fit the neighbourhood model, as do the locations that still regard themselves as separate "villages" despite being within the Bath City boundary, Larkhall, Weston and Combe Down.

This very quick look demonstrates that there is nothing new in New Urban Principles; rather that they are an old craft, forgotten and overlooked in the post-war flatten and rebuild frenzy that gave us sprawling housing estates like Sladebrook and Southdown with long walks (or a car ride) to the shops, and no central meeting places.

The Outcome

The results of the students' work were presented to the Mayor, the Chairman of the Council and members of the public, and their drawings were made available to the public for two weeks afterwards in the Bath Society Hall. The University has now been in touch, to let us know that they submitted their work to the Congress for the New Urbanism's Charter Awards, where it gained an "Honourable Mention" which they are very pleased about because most of the CNU awards go to American schemes that have been or will be built. We are told that there is world-wide interest in CNU awards, which will be good for the University, and will bring Bath to a wide audience.

The summary information that gained the award is also on-line, as is the background information video, now made available on YouTube.

Go back to top index

About The University

At the end of March 2011, Watchdog sent a representative to the University of Notre Dame in Indiana in response to an invitation to take part in a colloquium entitled "Modernity, Social Change and Tradition in Historic Bath". This gave us the opportunity to see for ourselves the campus and the facilities available to the students.

The location came as something of a surprise. South Bend, which houses the university, is approximately 120 miles outside Chicago, and with its own regional airport and railway terminus is comparable in size with Bristol. The university student population is just over twice the combined student populations of Bath Spa University and the University of Bath, on a campus roughly the size of Saltford complete with shops, a hotel, a cathedral (it was too big to describe as a church, see picture), an 80,000 seater football stadium (American football) two ornamental lakes, a 9-hole golf course and its own bus station.

The location came as something of a surprise. South Bend, which houses the university, is approximately 120 miles outside Chicago, and with its own regional airport and railway terminus is comparable in size with Bristol. The university student population is just over twice the combined student populations of Bath Spa University and the University of Bath, on a campus roughly the size of Saltford complete with shops, a hotel, a cathedral (it was too big to describe as a church, see picture), an 80,000 seater football stadium (American football) two ornamental lakes, a 9-hole golf course and its own bus station.

The university has colleges for Business, Arts, Engineering, Science and Law as well as Architecture.